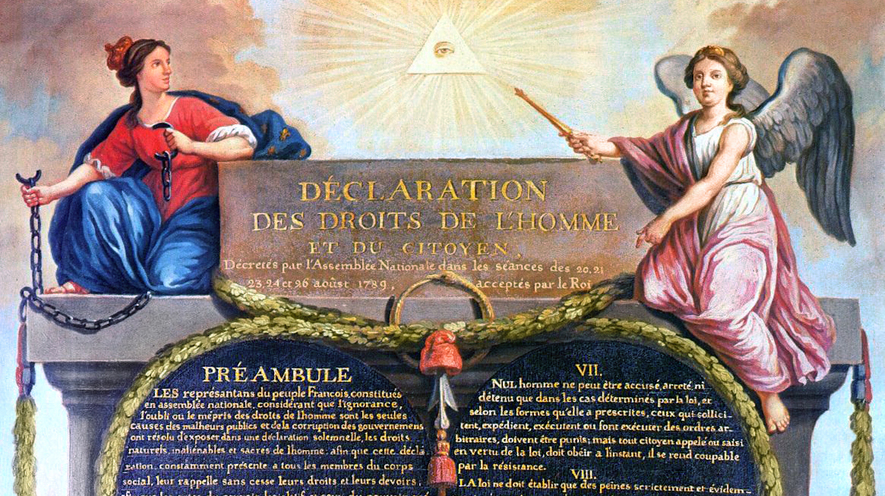

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (the French Declaration of Rights) was passed by the National Assembly on August 26th in 1789, which laid out the French absolute monarchy for the first time transmitted to a new plan of a constitutional government holding principles of the natural rights of man and citizen of a nation. It is acknowledged that the declaration is the significant achievement of the French Revolution and the goal of the Enlightenment. However, in order to excess the understanding of a bill of rights, in this paper, one of most lasting important aspects in terms of Human Rights will be investigated in comparison with the other two historical declarations of Human Rights, which are the Declaration of Independence (The US 1776) and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (the UN 1948). The aim of this analysis is to understand the use of language in those three declarations and therefore come to a conclusion of the role of Human Rights in the contemporary phase.

Is that a matter when important declarations of Human Rights merely include those words such as “men”, “women” or “human beings”? In the first Article of the French Declaration of Rights, it declared, “Men are born free and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility.”[1] It is known that the time when this document was written is right in the massive movement of the Enlightenment and the influence of the American Declaration of Independence written by Jefferson in 1776. In details, The Declaration of Independence 1776 recognized “the unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united State of America” in the preamble addressed in the Congress, July 4, 1776.[2] Whereas, there had no appears of “France” or “French” in the French Declaration’s articles. While it is considered the embrace of political ideology, some critics suppose the advancement of the declaration in its holistic Enlightenment beliefs. This is radically reoriented and embraces the notion of humanity. Not yet to answer the ambiguous understanding of the use of language, this means that whether or not the French Declaration of Rights can foreshadow its paradox. First and foremost, this originated the debates amongst the women and the society in France. So the issue caused a broader humanistic challenge and required a type of reform in making the equality of gender. That is the reason why the Declaration of the Rights of Woman (Olympe de Gouges 1791) was published.

In addition, in the early 1790s, the contentious issue was of slavery. In 1791, the slave riots in Saint-Domingue promoted the tension and accused the French of non-humanity in the “extreme form of the denial of right”.[3] Subsequently, “the National Assembly did temporarily grant citizenship rights to free men of colour in 1791” in order to decrease the chaotic situation; until 1848 the revolutionary government enfranchised all men and abolished slavery.[4] In order to broaden the view on this, Lynn Hunt called that is “a revolutionary document” and thus the legacy of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 was resonated in the worldwide in terms of its preeminence. She pointed out the deliberation in the use of the French Declaration of Rights of the UN by saying that “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” [5] Also, in the Enlightenment’s philosophy the concept of “the rights of man” and the natural rights” were reoriented and its aims were to mention the central aspect of the universe, so that was human and coined into the abstraction of a constitutional government in a new recreational form of the hereditary monarchy. One more persuasive evidence that Lynn focused on is the Declaration of Independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam written by President Ho Chi Minh in 1945 when he cited the words from the two aforementioned documents including The Declaration of Independence of the American in 1776 and The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of the French in 1789, he saw the advancement in those two writing in terms of the “natural rights” of every human person.[6]

In conclusion, The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen is the legacy of the past and its contemporary values. In the analysis above has shown two different aspects of the document. It is, however, the product of human being in the past and is demonstrated the consciousness of the urged need in recognizing the basic of human rights. In terms of the human flourishing, this totally results in the historic event of the human beings and becomes the standard for every single human person embraced the dignity themselves and the respect of one another universally.

[1] “The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen”, September 1, 2017, https://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/295/

[2] “The Declaration of Independence”, September 1, 2017, http://www.ushistory.org/declaration/document/

[3] Denise Z. Davidson. “Feminism and Abolitionism,” in The French Revolution in Global Perspective. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press 2017), 103. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com

[4] Davidson, “Feminism and Abolition,” 103.

[5] Lynn Hunt. “The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, August 1789: A Revolutionary Document.” Revolutionary Moments: Reading Revolutionary Texts. (2015): 77-84, doi: 10.5040/9781474252669.0016

[6] Hunt, “the Declaration,” 77-84.

Bibliography

Desan, Suzanne, Hunt, Lynn, and Nelson, William Max. The French Revolution in Global Perspective. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013. Accessed September 1, 2017. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy2.acu.edu.au/lib/acu/reader.action?docID=3138450

Hunt, Lynn. “The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, August 1789: A Revolutionary Document.” Revolutionary Moments: Reading Revolutionary Texts., (2015): 77-84. doi: 10.5040/9781474252669.0016

The Declaration of Independence, The Declaration of Independence – The Want, Will, and Hopes of the People, accessed September 1, 2017, http://www.ushistory.org/declaration/document/

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity – Exploring the French Revolution, accessed September 1, 2017, https://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/295/